Last summer I went on a roadtrip in Central Europe, traveling by campervan. When I was traveling through the Austrian alps i realized how close I was to Hallstatt. A place I knew from several documentaries abut the amazing Celtic Broze Age finds made there, so I just had to make a stop.

The small town of Hallstatt are as I mentioned located in the Austrian alps, about a hours drive from Salzburg. The town lies on the shore of a lake with high mountains behind it. The only way to reach it used to be by boat or by climbing the mountain paths and entering the town through the attics of the houses.

In the 1890s a road was constructed so that visitors today can arrive by car or even bus.

The reason for building a town in such an inaccessible place was the salt mine, that has been in use for at least 7000 years making it the world’s oldest salt mine that is still operational.

Above the town in the mountain lies a valley reachable by funicular from the town. The valley offers quite spectacular views of the town, lake and the surrounding mountains, which would make it worth the trip just for that.

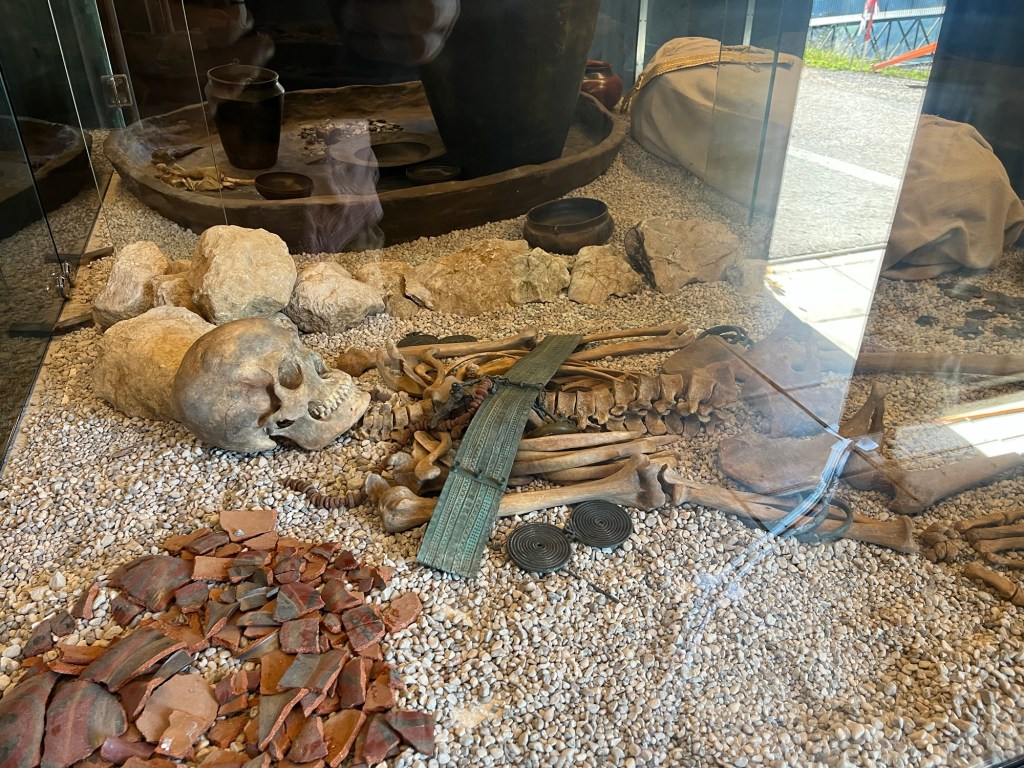

The valley contains a particularly rich Bronze Age and Iron Age grave field where 1045 people were buried. During the Bronze Age the culture here belonged to the urn field culture that existed between 1300–750 BC. The graves from this period are cremations which the ashes placed in funerary urns that gave the culture its name. This culture was dominant in Central Europe and borders that of the Nordic Bronze Age culture and the Atlantic one.

The urn field culture was succeeded by the Hallstatt Culture 8th-5th centuries BCE that got its name from this place. We are now in the early Iron Age and the members of this culture are considered to be a speakers of Proto-Celtic languages.

Many interesting archaeological finds have been made among the graves of highly decorated swords, daggers and many other things of beauty, as their skill in metal crafts was very high.

The reason for the richness of the graves here are the salt mine. It is located at the top of the valley and visitors can walk there from the end station of the funicular.

Salt was just as now an important commodity. But back then it was much more valuable. Salt is essential in preserving food like meat, fish and vegetables. So by trading it the people here got incredibly rich. Someone also made the brilliant idea to raise pigs in the valley then drying and salting the hams here for export. It is thought that the Romans learned this practice from the celts and then spread the practice throughout the Mediterranean giving us to day many different forms of this delicacy.

The salt here was discovered already by humans during the Stone Age, most likely by tasting saltwater springs. Real mining started first during the Bronze Age and they continued to dig themselves deeper down into the mountain. During the Iron Age new technique of mining the salt was invented. The male workers would cut out large horseshoe shaped blocks of rock salt from the walls.

These blocks would then be carried out of the mine by the women. The shape made them easier to carry. For some reason work seem to stop for a time during the 500s BCE. The reason for this is unknown, but a lot of the graves are looted and it might have happened during this period. Salt is still mined during Roman times but then temporarily stops to be resumed in the 13th century.

3100 years ago during the Bronze Age, a major accident happened in the mine. Excessive rainfall caused a mudslide to fill parts of it burying everything there.

The salt preserve organic matter very well and archaeologists found a perfectly preserved wooden staircase that was 8 meters long and 1.5 meters wide. When it was buried it had been in use for around 100 years. This is the oldest preserved wooden staircase in the world.

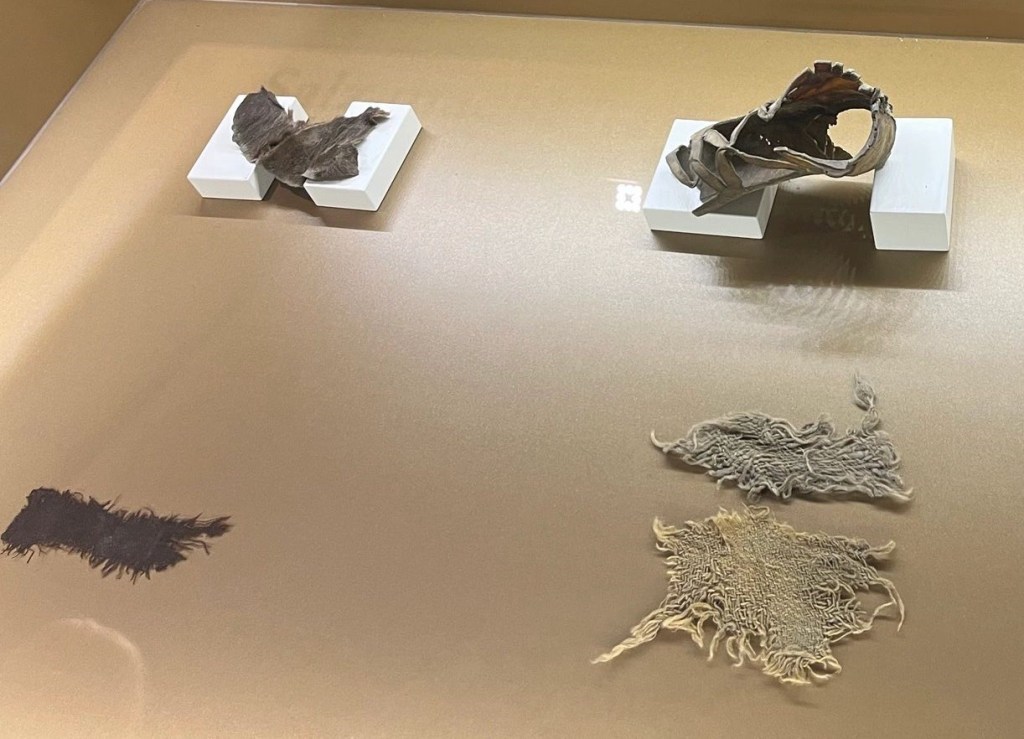

Along with the staircase a lot of other important finds were discovered, for example textiles, leather, pelts, shoes, backpacks and torches.

For visitors to enter the mine one have to join one of the guided tours. It is well worth the cost, but it is not for people faint of heart as you have to use two wooden slides to get deeper down into the mines.

Lämna en kommentar